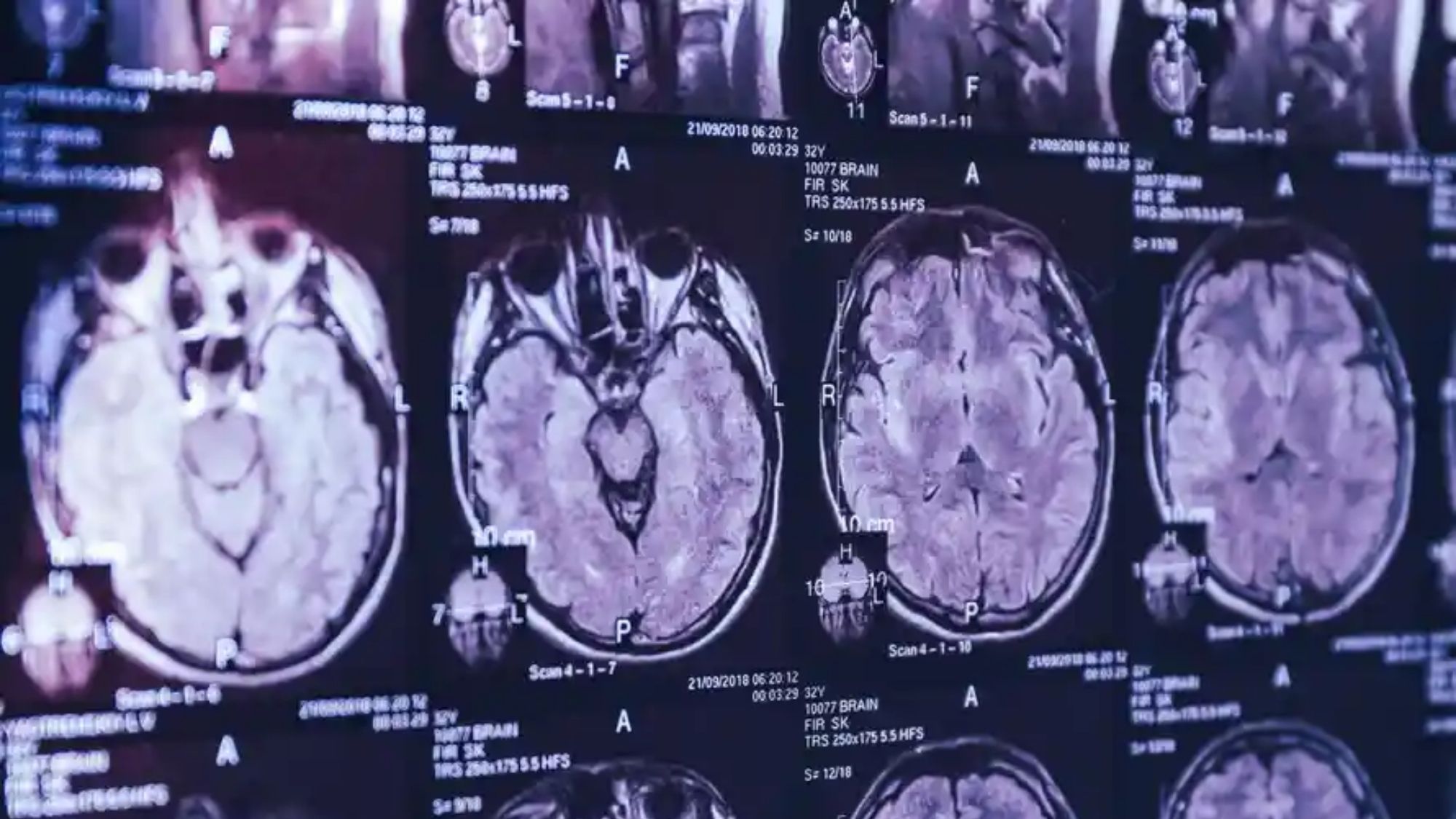

A rare degenerative brain disease baffles doctors across Canada, with patients suffering from a variety of symptoms from physical debilitation to hallucinations.

DOCTORS in Canada are baffled about a new and rare degenerative brain disease that has been occurring among patients from New Brunswick’s bucolic Acadian peninsula.

Roger Ellis collapsed at home with a seizure on his 40th wedding anniversary. In his early 60s, Ellis, who was born and raised around New Brunswick’s Acadian peninsula and was working as an industrial mechanic, had been healthy until that June.

His son, Steve Ellis, said that after that fateful day his father’s health deteriorated rapidly.

“He had delusions, hallucinations, weight loss, aggression and repetitive speech,” he said.

“At one point he could not even walk. So in the span of three months, we were being brought to a hospital to tell us they believed he was dying—but no one knew why,” he continued.

BBC News said Roger Ellis’ doctors first thought it was Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [CJD], a fatal and rare degenerative brain disorder that sees patients present with symptoms like failing memory, behavioral changes and difficulties with coordination.

One widely known category is Variant CJD, which is linked to eating contaminated meat infected with mad cow disease.

CJD also belongs to a wider category of brain disorders like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and ALS, in which protein in the nervous system become misfolded and aggregated.

But Ellis' CJD test came back negative, as did the barrage of other tests his doctors put him through.

His son says the medical team did their best to alleviate his father's varying symptoms.

But doctors were still left with a mystery: what was behind Ellis's decline?

Last March, the younger came across a possible - if partial – answer from Radio Canada, with the broadcaster obtaining a copy of a public health memo that had been sent to the province’s medical professionals warning of a cluster of patients exhibiting an unknown degenerative brain disease.

"The first thing I said was: 'This is my dad,'" he recalls.

Roger Ellis is now believed to be one of those afflicted with the illness.

Isolated case

The neurologist with Moncton's Dr Georges-L-Dumont University Hospital Centre says doctors first came across the baffling disease in 2015.

At the time it was one patient, an "isolated and atypical case", he says.

But since then there have been more patients like the first - enough now that doctors have been able to identify the cluster as a different condition or syndrome "not seen before."

The province says it is currently tracking 48 cases, evenly split between men and women, in ages ranging from 18 to 85.

Those patients are from the Acadian Peninsula and Moncton areas of New Brunswick. Six people are believed to have died from the illness.

Most patients began experiencing symptoms recently, from 2018 on, though one is believed to have had them as early as 2013.

Dr. Marrero says the symptoms are wide ranging and can vary among patients.

At first, there can be behavioral changes like anxiety, depression and irritability, along with unexplained pain, muscle aches and spasms in previously healthy individuals.

Frequently, patients develop difficulties sleeping - severe insomnia or hypersomnia - and memory problems.

There can be fast-advancing language impairments that make it difficult to communicate and hold a fluent conversation - issues like stuttering or word repetition.

Another symptom is rapid weight loss and muscle atrophy, as well as visual disturbances and co-ordination problems, and involuntary muscle twitching.

Many patients need the assistance of walkers or wheelchairs, while some develop disturbing hallucinatory dreams or waking auditory hallucinations.

Several patients have presented with transient "Capgras delusion", a psychiatric disorder in which a person believes someone close to them has been replaced by an impostor.

"It's quite disturbing because, for instance, a patient would tell his wife: 'Sorry ma'am, you cannot get in bed, I'm a married man' and even if the wife gives her name, he'd say: 'You're not the real one,'" Dr. Marrero says.

There is no treatment, beyond helping to alleviate the discomfort of some of the symptoms.

For now, the theory is that the disease is acquired, not genetic.

"Our first common idea is that there's a toxic element acquired in the environment of this patient that triggers the degenerative changes," says Dr. Marrero.

One theory is chronic exposure to an "excitotoxin" like domoic acid, which was linked to a 1987 food poisoning incident from mussels contaminated with the toxin from the nearby province of Prince Edward Island.

University of British Columbia neurologist Dr. Neil Cashman said they are also looking at another toxin - beta-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) - which has been implicated as an environmental risk in the development of diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

But Dr. Cashman cautions the current list of theories "is not complete."

"We have to go back to first principles, go back to square one," he says. "At this point basically nothing can be excluded."

(RdlC)

Tags: #Canada, #medicine, #braindisease