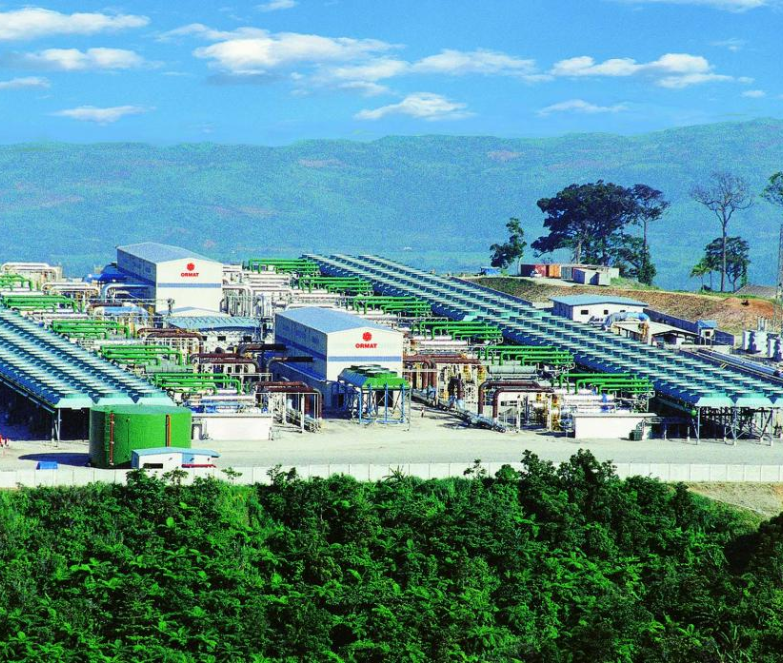

The Energy Development Corporation (EDC) has submitted a formal letter of intent to the Department of Energy (DOE), heralding the phased decommissioning of the 129-MW Upper Mahiao Geothermal Power Plant in Leyte.

The plant, which entered commercial operations in 1996, will begin decommissioning in 2026 and conclude by 2029. EDC declares the facility has reached the end of its operational lifespan.

On the face of it, this is a bold declaration. Upper Mahiao is among the older geothermal assets in the country, having been commissioned in 1996.

EDC’s decision reflects both the realities of ageing infrastructure and its stated ambition to repurpose the site. Vice-President Ryan Velasco confirmed that a feasibility study will be carried out to explore redevelopment of the site.

Meanwhile, EDC has already flagged its broader upgrade program for its Leyte geothermal complex, with particular mention of expanding the 180-MW Mahanagdong plant and eventually replacing Upper Mahiao with a facility of at least 200 MW.

In terms of upgrading and adapting, this move deserves praise for its forward‐looking mindset.

Geothermal energy is a strategic cog in the Philippines’ clean-energy transition: EDC states it is the largest 100 % renewable-energy company in the country.

Retiring an older asset and replacing it with a more capable one, makes sense if executed well. The announced upgrades for Leyte, including new wellhead technologies and binary modular systems, have already been flagged in recent reporting.

Yet the decommissioning also raises some pressing questions and not all are being addressed publicly.

For one, decommissioning a plant that still have an output of over 100 MW suggests that upstream resource decline or cost-inefficiencies are catching up with operations.

The plant’s original capacity is cited at 125 MW. Will the new replacement really deliver 200 MW as envisioned or is that more aspirational than realistic?

Moreover, the transition period (2026-2029) will need to be managed carefully to avoid capacity shortfalls in the Visayas grid, where the Unified Leyte complex plays a key role.

Past events underscore that even established geothermal plants require resilience efforts: after Typhoon Yolanda, EDC had to restore units at its Leyte plants.

For many, the decommissioning of Upper Mahiao should be seen as a strategic pivot rather than a retreat if it delivers upgrade, capacity expansion and improved efficiency.

The ambition to raise output from around 130 MW to 200 MW is significant, and the planned feasibility study is welcome.

But the devil is in the execution: geothermal is complex, resource-intensive, and lifespan matters. If the redevelopment project stalls, the region may face both stranded assets and supply vulnerability.

In other words, this is a moment of opportunity and risk.

EDC is wise to emphasize the site’s future repurposing rather than simply scrapping it. It appears that the company sees geothermal not as a sunset industry, but as evolving.

But given the Philippines will need major renewable capacity in coming years, what matters most is how quickly the transition happens, what capacity is restored, and whether communities and grid stability are safeguarded in the interim.

#WeTakeAStand #OpinYon #OpinYonNews #DOE #EDC