Festivals and religious practices have long been integral to the Filipino identity, deeply intertwined with the nation’s faith and spirituality.

Behind these cherished celebrations lie stories of faith and resilience deserving of preservation.

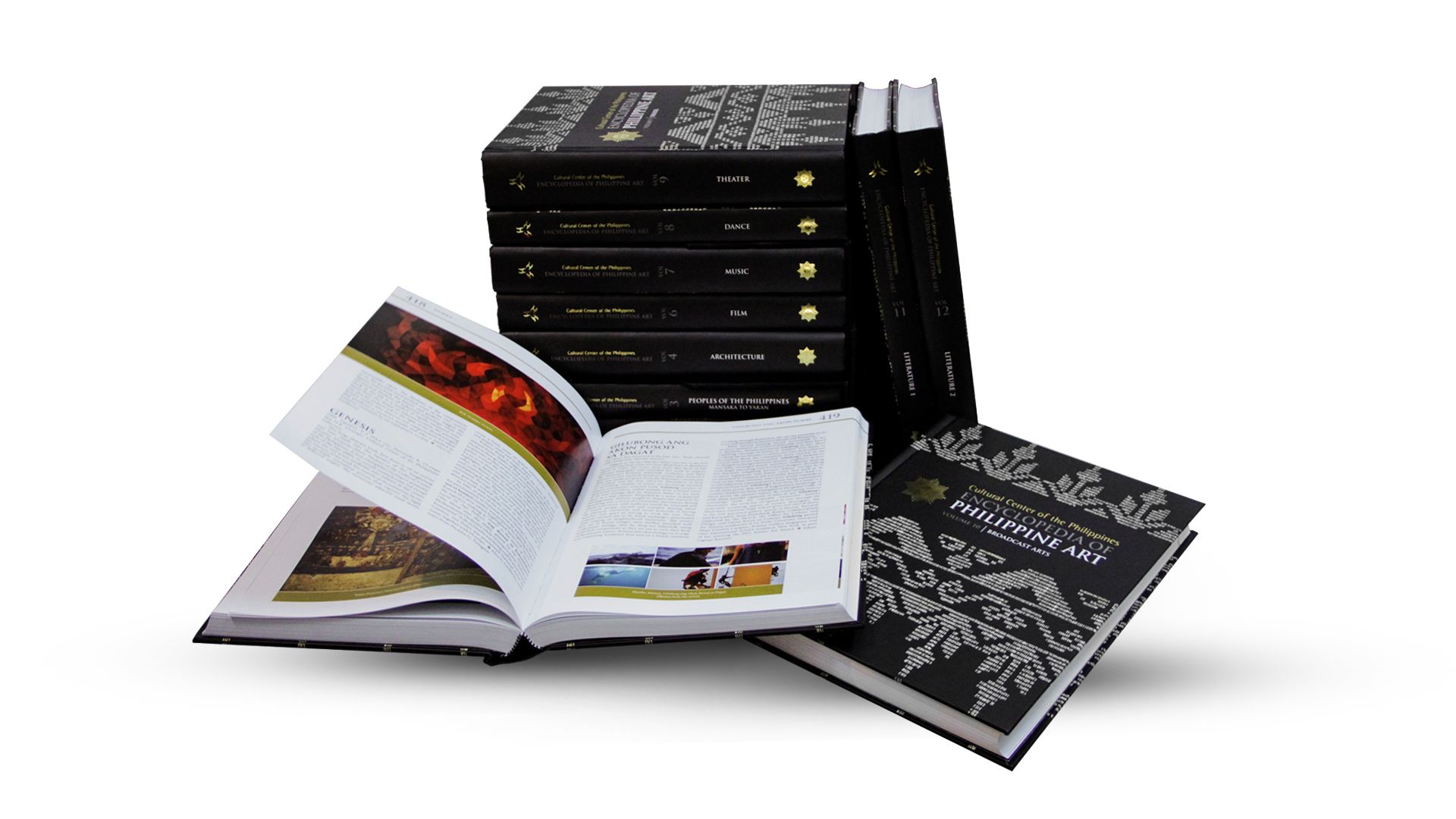

The CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Arts (CCP EPA), the country’s most authoritative and comprehensive source of arts and culture knowledge, documents these narratives, ensuring that the spiritual heritage of Filipinos is passed on.

“Filipino faith is woven into the fabric of our traditions, and we must preserve these sacred practices for generations to come. Through the CCP EPA, we document and share our religious heritage, honoring our history and the enduring spirit that shapes our identity. By celebrating and passing down these stories, we ensure that our culture transcends time, leaving a transformative impact for centuries to come,” said Cultural President of the Philippines (CCP) president Kaye Tinga.

The CCP EPA reflects on the spiritual significance of these sacred observances in the country through its entries on religious feasts and events celebrated every January.

Here are some of the Philippines’ fests in January:

TATLONG HARI (THREE KINGS) OR THE EPIPHANY

Tatlong Hari, also known as the Epiphany, honors the revelation of Jesus Christ through the eyes of kings Melchor, Caspar, and Balthazar.

In Floridablanca, Pampanga, three men dressed in regal clothes walk alongside a procession of the Virgin and attend mass. Three boys in crowns and capes parade on horses in Cavinti, Laguna. They are showered with candies and coins as young ladies escort them. Meanwhile, the municipality of Gasan, Marinduque honors the three kings with a play after a morning mass.

FEAST OF THE BLACK NAZARENE

The Black Nazarene’s dark color spurred many theories. One said it was made to reflect the complexion of native Mexicans. Another claimed the Black Nazarene was a casualty of a fire during its voyage to the Philippines. Miraculously surviving the alleged disaster only fueled its reputation.

The Augustinian Recollects brought the life-sized image of the Black Nazarene on May 31, 1606, according to the CCP EPA. Initially, it was enshrined in San Juan Bautista Church in Bagumbayan (now Rizal Park). Upon the request of Manila’s archbishop Basilio Sancho de Santa Justa, it was moved to Quiapo Church in 1787. This transfer and the feast of the Black Nazarene are commemorated through a grand procession called “Traslacion”.

Every January 9, millions of devotees flock to Quiapo to attend the Traslacion.

FEAST OF SANTO NIÑO OR HOLY CHILD JESUS

The Santo Niño’s historical significance lies in the theory that Ferdinand Magellan brought it in 1521. Dressed in the traditional costume for Spanish children of the late 16th and 17th centuries, the Holy Child’s right hand holds a scepter to impose justice. The other carries an orb with a cross, describing its power over all creations and Spain’s sovereignty over its vast territory.

Magellan arrived in Cebu and a beautiful Santo Niño statue was presented to Rajah Humabon’s wife Hara Amihan. As she was baptized with her Christian name Juana, she wished for the image to be gifted.

Juana danced the sulog (tides) with her handmaidens, birthing Cebu’s Sinulog Festival, the Dinagyang Festival of Iloilo, Kalibo’s Ati-atihan, and the Feast of Santo Niño de Tondo.

CEBU’S SINULOG FESTIVAL

Besides the Sinulog dance performed every third Sunday of January, Cebuanos commemorate the occasion by selling candles and services. The candle vendors’ dance was far from the frenzied version according to the CCP EPA. Their hips would subtly sway as they waved their hands with the candles bought by devotees.

A theatrical style emerged in 1980, following a new policy by the Augustinians and the Ministry of Youth and Sports Development. Now part of Cebu’s culture, choreographers compose various formations. Each Sinulog demonstration has one or more dancers carrying a statue of Santo Niño, attracting about 1.5 to 3 million people to Cebu City.

DINAGYANG FESTIVAL IN ILOILO

In Iloilo City, Reverend Father Ambrosio Galindez introduced the devotion to the Holy Child in 1967. Its prized festival, Dinagyang, began in 1968 when Fr. Sulpicio Enderez of Cebu gifted the San Jose Parish in Iloilo City a replica of the original Santo Niño de Cebu. Ilonggos welcomed the image by parading down the streets wearing colorful outfits.

Apart from tribal dancing in elaborate costumes, Dinagyang Festival is an exhibition of the Ilonggos’ kindness. Iloilo, dubbed the City of Love, offers tourists and people dishes such as pancit molo and chicken inasal.

KALIBO, AKLAN’S ATI-ATIHAN FESTIVAL

Roman A. dela Cruz’s Song of the Ati-ati (1974) describes Kalibo’s Ati-atihan Festival in 609 lines. The festival stretches back to pre-colonial times when the Atis, the original inhabitants of Panay Island, welcomed the Malay settlers. Ati-atihan Festival commemorates this interaction as depicted in Song of the Ati-ati.

The song narrates the preparation of the dancers, as recorded in the CCP EPA. They paint themselves with uling (charcoal) and turn ordinary implements like kettles into musical instruments. As the song progresses, onomatopoeic words like “bong bong” and “tog tog” reproduce the rhythm and beat of the Ati-atihan Festival.

Song of the Ati-ati is the first published poem in English replicating the vibrance of the festival.

THE FEAST OF SANTO NIÑO DE TONDO

Wooden replicas of Magellan’s Santo Niño are paraded in a Catholic procession in Tondo, Manila. Believed to grant miracles, the statues are celebrated through a festive dance before being blessed by a priest. Worshippers also manifest success, good luck, and protection as they dance while carrying their images of the Santo Niño.

Apart from commemorating the Philippines’ conversion to Christianity, the Feast of Santo Niño de Tondo remembers the innocence and virtues upheld by Jesus Christ as a child.

CCP EPA: A CULTURAL TREASURE

Researched by over 500 respected scholars and experts from the country’s top universities and research institutions, the CCP EPA is the most comprehensive resource on anything and everything artistic and cultural. With its latest edition, the CCP EPA has over 5,000 articles in its 12 volumes. Meanwhile, its digital edition (CCP EPAD) holds over 5,000 articles and hundreds of video excerpts from dances and musical performances from the CCP archives.

Since printing its first edition in 1994, the CCP EPA has kept true to the Center’s mission of championing Philippine arts and culture by being an invaluable record of Filipinos’ artistic feats and cultural practices.

Subscribe to the CCP EPAD through its official website epa.culturalcenter.gov.ph/encylopedia with rates from P75 per month to P675 per year. Email epa@culturalcenter.gov.ph to purchase a copy of the CCP EPA print edition and/or USB.

#WeTakeAStand #OpinYon #OpinYonNews #CCPEPA #FiestasinPH #ReligiousPractices